Apraksin Blues № 15.

2008 - THE HEART OF THINGS

THE BEAUTIFUL MALADY OF COLLECTING. INTERVIEW WITH RUVIM BRAUDE

Irina Rapoport (translation

by James Manteith)

You draw, you draw,

it'll be to your credit.

Bulat Okudzhava

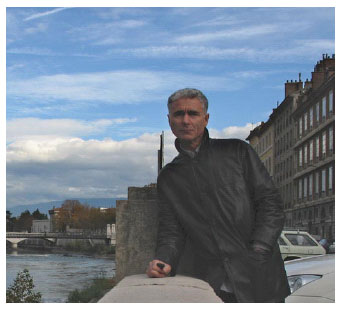

RUVIM BRAUDE

San

Francisco, Monterey Boulevard. I

approach a house that sooner recalls a miniature castle. It stands on a hill overlooking the ocean,

today as still as blue glass. Only white

sailboats in the distance enliven its placid smoothness. An improbable peace!

The

door is opened by the house's master—an energetic, graying, highly charming

man. It was he, Ruvim Braude, who

gathered in the house (later helped by his wife Inna) a unique collection of

the paintings and drawings of Leningrad artists of the second half of the 20th

century. Entering here, you immediately

feel the atmosphere of the intense life of Leningrad, in which the artists

lived and struggled, defending their right to express themselves in art.

The fight to establish an independent

art had begun in Leningrad by the 1950s and reached a peak in the 1970s. Its best-known events proved to be the famous

exhibits at the I. Gaz Palace of Culture in 1974 and at the Nevsky Palace of

Culture in 1975, held in response to the so-called "bulldozer"

exhibit in Moscow in 1974. The Leningrad

artists called their movement "Gaza-Nevsky culture" or Gazanevshchina. As a result of this movement, there emerged a

"Fellowship of Experimental Exhibitions" — TEV.

By the 1980s, due to pressure from the

authorities, many of the participants in Gazanevshchina were forced to

emigrate. The rest, along with artists

of the younger generation, organized as TEII, "Fellowship of Experimental

Fine Arts". TEII formed the basis

for a third formation — the Fellowship "Free Culture" along with the

art center "Pushkinskaya-10".

"Pushkinskaya-10", thanks to

the noble and tireless work of leading artists Sergei Kovalsky and Yevgeny

Orlov, has turned into a major cultural center, now known in many countries

throughout the world. The center has

expanded its activies to other areas of culture and has also created a

permanent Museum of Non-Conformist Art.

At "Pushkinskaya-10", great

care is shown to the cultural heritage of the Gazanevshchina artists. In 2004 in Petersburg, at the Central

Exhibition Hall "Manege", a "Festival of Independent Art"

took place, dedicated to the thirtieth anniversary of the exhibit at the Gaz

Palace of Culture. The organizers did a

tremendous job, gathering materials and showing the work of all the

participants of Gazanevshchina and "Pushkinskaya-10", connecting the

past and the present of the non-conformist art of Leningrad-Petersburg.

Braude's

collection in San Francisco happens to be devoted mainly to Leningrad

non-conformist artists. Assembled very

thoughtfully, it presents artists of many different directions. No artist, no work is here by chance. Each work bears the imprint of its author's

identity and has its own place in the collection. Rarely can one see such a clearly focused

private collection.

IRINA RAPOPORT (IR) — Ruvim, tell me, please, what caused you to start

collecting? Fine art probably wasn't a

central interest in your family. Your

grandfather was the chief rabbi of Leningrad.

RUVIM BRAUDE (RB) — The turning point and the beginning of my interest —

no, passion for art — was the exhibit in 1975 at the Nevsky Palace of Culture,

to which a friend happened to take me.

This had an aesthetic, moral, political impact that qualitatively

changed by life. I was also stunned by

viewers' interest in this exhibit: such

a conscious, collective interest in art.

Remember the unprecedented lines for the exhibit? I began to dream that one day I could have

one or two of those works.

Unfortunately, at that time I knew nothing about the apartment exhibits

of the 1970s.

IR — When did you start thinking about your own collection?

RB — In 1981 I happened to visit an emigrant household in Long Island where

all the walls were hung with works by non-conformist artists. This immediately awakened assocations in my

memory and a thought crossed my mind about a potential chance for

collecting. That same year, I learned by

chance about an exhibit of Y.Abezgauz at a synagogue in New Jersey. I remember him from the Nevsky exhibit, and

with my meager funds acquired his graphic work "Again a Pogrom. What's to

be Done?"

IR — So a chain of "coincidences" led you to the idea of

collecting. What was the first painting

in your collection?

RB — "Sabbath", by Alexander Manusov (Ill. 1). I still have a sense of awe when I look at

it.

IR — A beautiful start! Sasha, whose

life ended prematurely, was a brilliant colorist, as this work shows. He has a very serious series on the theme of

the Old Testament and the Holocaust.

1. A.

Manusov, Sabbath

Yes,

the art of Gazanevshchina truly left a deep trace in your mind. The well-chosen works by its participants, as

well as by members of the "ALEF" group that emerged from it, have

made the collection very focused.

RB — But I didn't limit myself, it just happened. And those weren't the only

"coincidences". An aquaintance

staying a few days in San Francisco met (again by chance!), in Chinatown, Alek

Rapoport and you. I remembered Alek's

art from Leningrad and just leaped at the opportunity to get to know him

personally.

The

late I.V. connected me with Zhenya Ukhnalyov, asking me to help him sort out

documents related to his stay as a guest in San Francisco. R.S., the widow of Sasha Manusov, acquainted

me with Sasha Gurevich, and this meeting was providential for both of us.

IR — You're a guardian angel for Gurevich's art. You've done everything a sponsor can do for

an artist: assembled a large collection

of his works, organized several exhibits at your home, presenting his art to

many viewers, part of whom in turn started getting involved in collecting. You also systematized his own collection and

organized the release of an outstanding album... You know, as Matisse's son said: "If it hadn't been a Shchukin, there

wouldn't have been a Matisse."

These words don't downplay the significance of the artist's creativity,

but express the well-earned thanks due to the sponsor.

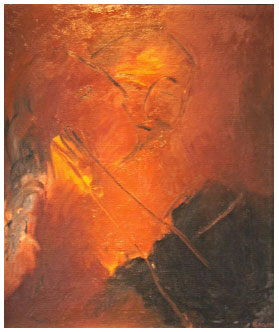

The

painting reproduced here (Ill. 2) is very typical for Sasha. In the words of the wonderful art historian

B.M. Bernshtein, the art of the past "weighs on an artist like the

atmospheric column." Most of

Gurevich's scenes and compositions suggest old painting, much as this one

relates to a painting by the 17th century French artist G. de la Tours. The scene has an interesting detail: beside the sitting musician, who has

Gurevich's own face, rests a handful of small change. It's a symbol of the sad lot of most artists

in all times.

2. A.

Gurevich, Hurdy-Gurdy Player

RB — And here is my favorite artist from Gazanevshchina and the ALEF group —

Alek Rapoport.

IR — Alek is my favorite artist, too.

"The soul of my soul," with whom we were connected in 35 years

of love. Probably in the passion, the

intensity, the seeking after truth, the religious doubts, in which he lived and

worked, can be found the reason for his early death while at work in his

workshop in San Francisco. As B.M.

Bernshtein pointed out in studying the cycle "Angel and Prophet",

it's even hard to understood what the artist expected, releasing his progeny

into this world: "In the veins of

the outwardly calm and wise artist streamed the blood of Biblical prophets,

visionaries and heralds of truth."

M.Lemkhin compared Alek with Atlas, who "didn't even think of

tossing the weight of great traditions from his shoulders — art for him was

primarily responsibility."

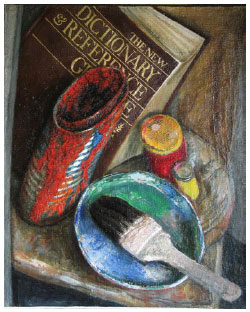

You

have representations of all the genres Alek worked in: Biblical, "Images of San

Francisco," self-portraits, still-lives (Ill. 3). Here is also "Self-Portrait" from

the 1950s, which Alek did while still quite young, and soldier drawings from

the period when he served in the army in Birobidzhan. You even have his "Composition with a

Kwakintle Mask" — a result of Alek's brief study of the cultural heritage

of American Indians.

3. A.

Rapoport, Still-Life with Dictionary

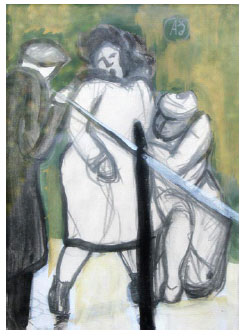

RB — I know Alek admired the work of Sasha Arefyev. I greatly value this drawing of his, the only

one in my collection (Ill. 4).

IR — Yes, it is rare. Sasha Arefyev

was one of the most significant figures of Leningrad non-conformism. He was a remarkable artist and a born

fighter. By the 1950s he had already

organized the "Order of Mendicant Painters". The subject of the drawing in your collection

is very typical. The theme of the

"victim's suffering and the tormentor's delight" runs through all his

work.

4. A.

Arefyev, Lady and Two Hooligans

RB — And here's another artist from Gazanevshchina and the "ALEF"

group — Anatoly Basin, quite a different nature: sad, harmonious, intimate

(Ill. 5). I recall that Alek appreciated

his work. Did they have different

teachers?

IR — Yes. Basin belonged to the

"Sidlin school", well-known in the 1950s and '60s. O.A. Sidlin (1909-1972) taught at Leningrad

art studios and had an enormous impact on a large group of artists, many of

whom joined the non-conformist movement.

Basin is a typical "Sidlinite". The teacher's idea was to concentrate on the

painting process itself (not on depicting emotions, literary scenes, psychology

and so on). Sidlin taught to convey

impressions of the world only as organized blotches of color. Before his death, he destroyed all his works,

because he thought only the creative process itself was important, not its

result. Sidlin's remaining students

still pronounce his name with breathy reverence.

5. A. Basin,

Two

One

of Alek's fellow students in N.P. Akimov's class at the Leningrad Institute of theater,

music and cinematography, as well as his friend, was Misha Kulakov. Living in Italy, he didn't directly take part

in the Leningrad non-conformist movement, but was also a non-conformist by

nature, as well as in the manner of his work.

He was one of the first among his peers to start studying the work of

Jackson Pollock and to make his own abstract compositions. Unlike most emasculated American abstraction,

his works are spiritual and carry a charge of unorthodox religiosity (Ill. 6).

6. M. Kulakov,

Composition

You

have many works by Yevgeny Ukhnalyov.

Alek called him an "honest artist." Among the works of his that I know,

"Boxcar" stands out (Ill. 7).

It has so much symbolism, which I don't always understand. Tell me about it, please.

RB — "Boxcar" is an extremely interesting triptych, which consists

of three separate parts. Zhenya himself

named this work with a line from a song by Galich, "Kadish": "And somewhere on the rails, on the

rails, on the rails — wheels, wheels, wheels, wheels..." An old,

fire-scorched boxcar, depicted in three parts that reflect three different

periods of the history of the 20th century, with the horrors of revolution and

civil worn; the Second World War and the Holocaust; the Stalinist repressions.

On

the left side of the boxcar is a symbol of the outgoing government in the

emblem of the czarist empire—a double-headed eagle—and sloppily written

fragments of revolutionary slogans:

"All power...", "Give..." and so on. In the distance is a dark smoky glow.

7. Y.

Ukhnalyov, Boxcar (triptych)

On

the middle part of the boxcar's wall is a Nazi swastika, fragments of

inscriptions in German, including a sprawling "only for Jews,

1944". The door is open, the boxcar

is empty, only over its edge hangs one end of a prayer shawl. In the distance is a row of gloomy camp

buildings and the smoking chimney of a crematorium.

On

the right side is the stamp of the October Railroad, an indication of the

destination, "Rechlag", 1948 and the camp number that was assigned to

the 18-year-old inmate Yevgeny Ukhnalyov.

In the distance is the "smoking hill of Vorkuta".

IR — Thank you, Ruvim. I think it's

Ukhnalyov's most significant work, and I'm glad it's in your collection.

Michael

Iofin came to the exhibit at the Gaz Palace of Culture as a 14-year-old

boy. It was then, he said, that he

realized that besides "Soviet" art there was also "different and

real" art. In his subsequent work,

Misha preserved the best traditions of "dissident" artists and became

an original and mature artist. His

typical topics deal with the artists of the past, as well as the theme of the

theatrical and dramatic carnival of Petersburg-San Francisco. He pays tribute to Petersburg in almost all

his works. But the painting in your

collection, Ruvim, focuses completely on the city's image and on conveying its

hidden spirit. I like this work very

much — "Pushkin over Petersburg" (Ill. 8).

The

northern, pale, quiet dusk. The stern

geometry of five horizontal lines: the

embossed line of the black lattice of iron railings powdered with snow; the

line of the single-toned, motionless surface of the Neva; the clear line of the

opposite shore; the unbroken line of slightly tinted buildings, the monotone

line of their upper boundary, enlived by the verticals of the spire domes,

chimneys. And over this landscape — the

horizontally soaring figure of A.S. Pushkin, overshadowing and personifying

Petersburg, the city mirage, frozen in its perfect and eternal harmony.

8. M. Yofin,

Pushkin over Petersburg

It

also seems remarkable to me how precisely the artist captured the idea of Peter

the Great, the principle of of strict regulation in constructing the city —

exemplary, proper, regular, geometrically calibrated. This work is so close to my heart!

RB — Several other artists in my collection have ties with Gazanevshcina —

V. Weiderman, Y. Abezgauz, S.

Ostrovsky. And with

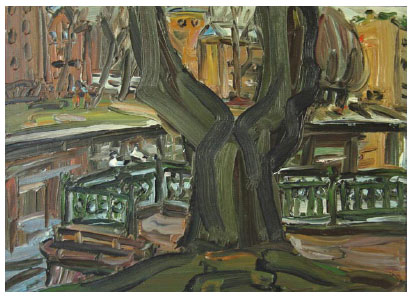

"Pushkinskaya-10" — V. Gerasimenko, Y. Tikotsky, B. Borsch.

9. B. Borsch,

Petersburg Landscape

IR — Boris Borsch may be one of Petersburg's best contemporary landscape

artists (Ill. 9). But this graphic sheet

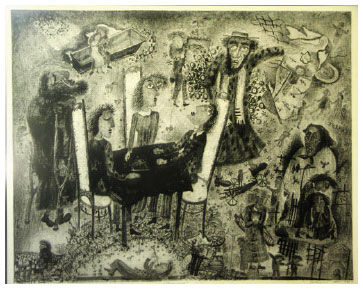

by Y. Tikotsky, "Fragment" (Ill. 10), strikes me as unusual. I don't know his work very well, but it seems

to me that this drawing, describing the details of routine life in a

"mestechko" townlet, falls outside of the main line of his work with

its Semitic theme and spirit.

10. Y.

Tykotsky, Fragment

Yakov

Feldman. Ruvim, I've never seen his work

before, and I like them very much. Who

is he?

RB — He's a young artist, born in Vitebsk, and now living in Jerusalem. It's interesting that his grandmother was a

niece of M. Chagal.

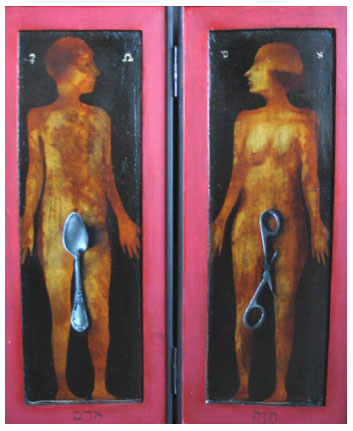

IR — His "Adam and Eve" (Ill. 11) is painted skillfully and its

technique reminds me of the work of the old masters — on a board, dark and rich

paint on the surface, the use of glaze.

Yet the traditional Biblical subject is brought nearer to modernity with

two kitsch details — Eve, instead of a fig leaf, is shielded by an image of scissors,

and Adam, by a spoon. It's a wonderful

acquisition, and a perfect fit for your collection.

11. Y.

Feldman, Adam and Eve

Ruvim,

in what direction will you continue — increasing the number of artists the

collection already represents, or will you emphasize Jewish artists, or

contemporary non-conformist art from Petersburg?

RB — I'm still collecting.

Fortunately, my wife Inna supports me.

She understands that collecting for me isn't a hobby but a passion, born

during the rise of non-conformist art.

It's a unique phenomenon in the history of development of art, a entire

movement arising as a consequence of unprecedented violence against art. The bitter irony is that art was born not in

spite of but because of persecution.

I

don't approach collecting for a purely aesthetic position — this I like, that,

no. I don't approach it with a

commercial outlook, either — selling the next day what goes up in price. What's important to me is art's combination

of historical, political, psychological, aesthetic significance. I think I'll expand my collection of artists

I already have. They're going through

transformations on their creative path, and I'll go with them, on the same

road. I also want to expand my collection

by acquiring art by contemporary artists connected with

"Pushkinskaya-10".

IR — How many works are included in your collection? What part of them are you able to display on

the walls of your home?

RB — About a hundred paintings, plus drawings and some sculpture, and

probably a third of that is on display.

IR — Do you acquire works, as did your famous predecessory P.M. Tretyakov,

while visiting the workshops of unknown artists?

RB — I guess so.

IR — Are artists generous with gifts?

RB — Yes, they're generous. The thing

is, some of my favorite artists also become favorite friends, with friendships

lasting many years. A gift is always

nice, but one has to keep in mind that an artist's work is also his way of

making a living.

IR — I'm delighted that your collection doesn't included any emasculated

Moscow "dip-art" — "art for diplomats", which almost no

Russian collection or gallery is without.

It worked out, in the 1960s and '70s, that namely diplomats in Moscow,

often with no understanding of art, became the main judges, the final authority

deciding whom to promote and whom to ignore.

In this way they tossed out worthy artists and advertised unworthy ones,

and thus did great harm to the objective assessment of art in general.

A

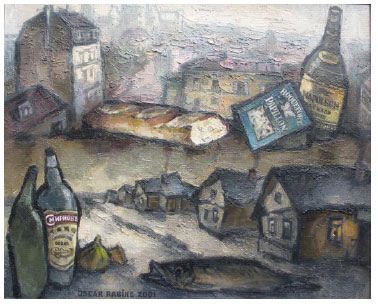

provocative question — do you have, for example, Oscar Rabin?

RB (in mock embarassment, lowering his eyes) — Yes, even two (Ill. 12).

12. O. Rabin,

Landscape with a Roll

IR — Yes, I understand. Rabin is a

purely Moscow phenomenon, looking back to the Wanderers. Unattractive paintings, monotonous

subjects: vodka and herring; bread and rolls;

shreds of newspaper or something else; the crooked cottages of the impoverished

provinces; poor, hopeless Russian... But

of course, his role as a mastermind and organizer of the non-conformist

movement in Moscow is beyond question.

RB — From what I know Moscow art, I can't relate to it as well, it's not so

close to me. But Petersburg art — it's

my own, personal art, I feel kinship with it.

IR — So, closing our brief conversation, I'd like to note that Ruvim Braude

is a very serious collector with his own firm concepts. His standard is his own, straightforward

assessment of a painting, without checking on others' opinion. It's very important that he loves and values

artists' own personalities, as well as their creations.

The

collecting of contemporary art is an occasion for special respect, in that the

collector doesn't know what commercial category the artist will end up in. The collector makes a personal investment in

art whose eventual fate is impossible to know in advance.

Sometimes

modern private collections grow to form large parts of museums, as happened

with the collection of professor Norton Dodge, which became the most complete

gathering of Russian non-conformist art, as part of the Zimmerli Art Museum in

New Jersey. Who knows what the current

collection of Ruvim and Inna Braude may turn into?

In

conclusion, I'd like to express heartfelt recognition to both of them for their

philanthropic work and to wish them never to be cured of the "beautiful

malady of collecting."

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Ill. 1

Alexander

Manusov (1947-1990)

Sabbath, 1989

Oil on canvas

100 x 120 cm

Ill. 2

Alexander

Gurevich (b. 1944)

Hurdy-Gurdy

Player, 2003

Oil on canvas

127 x 94 cm

Ill. 3

Alek Rapoport

(1933-1997)

Still-Life

with Dictionary, 1982-1997

Mixed media

on canvas

91.5 x 71 cm

Ill. 4

Alexander

Arefyev (1931-1978)

Lady and Two

Hooligans, 1955

Gouache,

pencil on paper

20 x 15 cm

Ill. 5

Anatoly Basin

(b. 1936)

Two, 1989

Oil on canvas

61 x 51 cm

Ill. 6

Mikhail

Kulakov (b. 1933)

Composition,

1975

Mixed media

56 x 76 cm

Ill. 7

Yevgeny

Ukhnalyov (b. 1931)

Boxcar

(triptych), 2001

Oil on canvas

91.5 x 183 cm

(three parts together)

Ill. 8

Michael Yofin

(b. 1959)

Pushkin over

Petersburg, 2003

Oil on canvas

23 x 30.5 cm

Ill. 9

Boris Borsch

(b. 1948)

Petersburg

Landscape, 1989

Oil on canvas

53 x 66 cm

Ill. 10

Yevgeny

Tykotsky (b. 1941)

Fragment,

1975

Dry quill,

paper

Ill. 11

Yakov Feldman

(b. 1969)

Adam and Eve,

2002

Oil on board

(diptych)

52 x 21.2 cm

(each part)

Ill. 12

Oscar Rabin

(b. 1928)

Landscape

with a Roll, 2001

Oil on canvas

61 x 76 cm

All contents © Apraksin

Blues./Все

содержания ©

Апраксин

Блюз.