Earning a Mandarin Square

David K. Hugus

Mandarin squares

are worthy of collection and study not only as textiles of extraordinary

quality and artistic merit. They also

embody a truly awe-inspiring level of intellectual content. Namely the area of intellectual

accomplishment will form my subject here.

Mandarin squares

are worthy of collection and study not only as textiles of extraordinary

quality and artistic merit. They also

embody a truly awe-inspiring level of intellectual content. Namely the area of intellectual

accomplishment will form my subject here.

Throughout the rule of the Ming (1368-1644) and Ch’ing

(1644-1912) dynasties, Chinese bureaucrats in the civil service and military

displayed their positions in the bureaucratic hierarchy by means of a square or

badge showing their rank. While size and

design were subject to modification along with the change in dynasties and

onset of various periods in each dynasty, the identifying silk squares

maintained general dimensions of about fourteen inches across in the Ming

period and twelve inches across in the Ch’ing period. The finely manufactured badges of rank were

displayed on the front and back of robes, usually silk, that covered the

ornately embroidered vestments worn for formal appearance at court. During the Ming period, badges were worn on

loose, free-flowing overcoats called pu-fu.

The Ch’ing pu-fu, made from dark-blue or black silk, fit tightly enough

to be worn on horseback, in keeping with nomadic tradition.

The squares

denoted rank with the representation of a bird or animal. Civil officials wore birds, whereas the

military wore animals. Birds symbolized

literary education and the art of flight, rising closer to heaven than

earth-bound creatures. A fitting

allegory for the top posts in the service of the Chinese emperor, whose title

declared him as the Son of Heaven!

Animals stood for ideas of military leaders’ martial ardor, courage and

ferocity.

The Chinese

bureaucratic system began to take shape more than two thousand years ago,

during the rule of the Chin dynasty (221 B.C.-207 B.C.). The creation of a bureaucratic apparatus

freed the emperor from the need to share power with a rival nobility. Under the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.),

this process became so pronounced as to indicate the need for a system for

choosing among the candidates who wished to serve the emperor. While the exact cause of the emergence of the

state examination system remains unclear, there is reason to believe it served

as a check on the emperor’s fondness for appointing his favorites to powerful

offices. The examination process thus

encouraged a merit-based orientation within the setting of absolute

autocracy. By the time of the T’ang

dynasty (618-907), a standard process existed for formally examining

applicants.

|

|

|

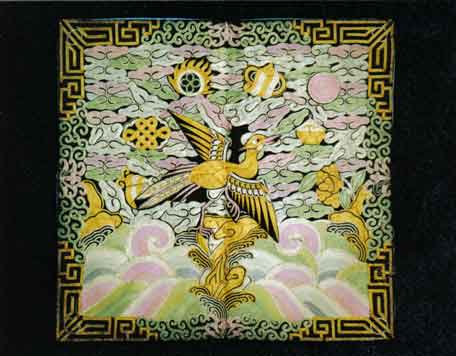

Golden pheasant, second half of the

19th century |

Although the

exams understandably covered a wide range of disciplines, they came in time to

focus increasingly on literature. By the

time mandarin squares were used to denote rank (before this, status was signaled

by the size and shape of an official’s hat), the exams included only one

subject—literature. But this made them

no less challenging! Quite the opposite

was true. An aspiring scholar’s

preparations to take part in the examinations normally began at age three, if

his parents could afford a tutor. He

first had to memorize a simple, 25-character poem. On the poem’s basis, he learned the rudiments

of writing and use of the writing brush, so as to progress to the more

sophisticated memorization of a poem containing a thousand unique

characters. Upon this task’s completion,

his main work began. He was expected to

master and know by heart the Four Books and Five Classics in their

entirety—nearly half a million characters in all. Through striving to perform this mammoth

task, at about age eight the student might attain formal enrollment in a

school.

Unlike schools

familiar to us, a classical Chinese school had nothing amusing, fun or pleasant

about it. Students were strictly

required to study alone and not speak with their classmates. Learning was based on drudgery, discipline

and fear. The slightest deviations from

fanatical studiousness were punished harshly and swiftly. Prospective officials had to master the

subject of submission to the powerful as thoroughly as literary standards.

The

schoolteachers tended to be failed candidates from the same exam process. Their work afforded neither respect nor

decent wages, so they had no cause to act either conscientiously or benignly. Chinese proverbs held a teacher’s primary

virtue to be severity. A young

applicant’s dedication was tested on each day of his battle to master and

reinforce his knowledge of the material.

Qualification for the first exam required the daily memorization of

about 200 new characters of text, as well as constant review of everything

learned to date.

A student who

achieved success at this tense stage could count on taking part in the district

exam. He had to report to this exam

early in the morning. The teacher

identified him and assigned him a numbered seat. This number was used for tracking when the

examination packet was submitted. When

the students were checked in, the proctor, a civil magistrate, locked the

examination hall, which was to remain shut throughout the testing session—a

full day, during which the student was expected to write two essays on the

themes of quotations from the Four Books and compose a poem with a set subject

and rhyme structure. The proctor could

not leave the examination hall until the papers were graded: this prevented him from taking bribes or

identifying students by seat number. The

names of candidates who passed were posted on the door of the district office

just after the exam.

The second round

was organized in the same way as the first, but required one essay on a theme

from the Four Books and another on a theme from the Five Classics, as well as a

verse composition. The student worked

his way through a series of four similar rounds comprising the first level of

examination. Students who passed the

district marathon became eligible for the prefectural examination—much the

same, but with three rounds instead of four.

Afterwards, about half of these students remained to attempt the

qualifying exam.

|

|

|

Mandarin duck, 1850s |

The qualifying

exam was conducted by the provincial director of studies. These officials were personally appointed by

the emperor and had direct access to the throne. This gave them a power and authority far

greater than their actual rank would suggest. As part of his duties, each director visited

every prefecture two times in a three-year period. During these visits, the director supervised

qualifying exams. Candidates entered the

examination hall by district. A district

official identified them. They were

searched for bribe money and crib notes.

If either were found, the candidate was disqualified and the finder of

the contraband was rewarded. The test’s

importance occasioned harsher discipline.

Infractions of the rules were noted with a special stamp on the

student’s paper. Such a mark virtually

guaranteed failure.

The stamps used were:

1. Leaving one’s seat.

(A candidate was allowed to leave his seat exactly once, either to drink

tea or visit the toilet. This required

the candidate to turn in and then retrieve his exam booklet. This took so much time that most candidates

brought and used their own chamber pots.)

2. Exchanging papers.

3. Dropping a paper.

4. Talking.

5. Letting one’s eyes wander and peeking at others’

papers.

6. Changing seats.

7. Disobedience (failure to follow a clerk’s

instructions).

8. Violating the regulations.

9. Humming (this often occurred during composition of

poetic rhymes and was quite distracting).

10. Incomplete (when a paper was not finished by

sunset, this stamp disallowed later additions).

Like the district test, the qualifying exam had four

parts, each given on a separate day.

Those who passed the final qualifying exam were notified in a message

brought by special courier. This was a

cause for great jubilation and feasting, as it meant the student had the right

to enter an official school to start preparing for true civil service exams.

The true civil service exams were also given at three

different levels over a three-year cycle.

For many, preparation for these exams proved a lifelong task. The average age upon completion of the final

civil service exams was about 35. This

meant preparation for the final triumph generally consumed about 32 years. But not everyone achieved success at such an

“early” age. Records from one

second-level test in the early 1900s show that 16 of those who passed were more

than 40 years of age, while one was 62 and another 83 years old.

The first civil service exam was administered by the

director of instruction for the province. The candidates tended to number about two

thousand. For any exam, about one

percent of candidates would pass, moving closer to the ultimate goal of a post

in the official bureaucracy. In

addition, successful students were recognized as members of the gentry. This gave them the right to erect a red sign

over their doors to signify their degree.

Their position also exempted them from local corporal punishment and

entitled them to government aid for further studies.

The second stage of the civil service exams was known

as the provincial exam. Under the Ming

and Ch’ing dynasties, the examination process was tightly regulated and

administered to combat favoritism. The

higher the level, the more stringent the security measures became. The imperially appointed examiners were

notified of their selection the day before they were to set out for the

examination. This procedure was intended

to minimize the possibility of examiners becoming known ahead of time and

offered bribes in exchange for favoring certain candidates. The penalty for taking a bribe was beheading.

Up to ten thousand candidates might report for the

test. At this level, the tests were

longer and more extensive. Three

sessions of about three days each were required for completion. The themes assigned for prose and verse

compositions measured candidates’ breadth of reading and depth of

comprehension.

The examination compound had no other function. It typically consisted of a walled enclosure

with a single entrance. The gates opened

onto a broad avenue with many lanes branching off to either side. Along one side of each lane were examination

cells. These were small, doorless

enclosures barely large enough to hold a single person. They had roofs but no furniture other than

three boards. One board acted as a

shelf, one as a table and one as a seat.

When all the candidates and examination officials were present, the

compound was sealed, not to be opened for any reason until after the

examination’s end. If a candidate died

from stress or exposure, his body was wrapped in straw matting and thrown over

the wall.

Prior to entrance on the first day of a test session,

each candidate was identified and strip-searched for contraband, texts and

model answers. Conversation was

categorically forbidden. Deaf-mute

attendants delivered and collected the questions. The candidate relieved himself either in his

cell or publicly, in the alleys.

The grading system was unbelievably complex. The compositions, written in black ink, with

the names and descriptions of candidates covered, were distributed among

several thousand clerks given only red ink, preventing the introduction of

changes to the originals. The clerks

copied the original versions, making it impossible for the graders to recognize

a candidate’s handwriting. The black and

red versions went on to proofreaders who verified the copies’ accuracy. Their corrections were in yellow ink. Next, the proofread copies were separated,

with the black version filed for safekeeping and the red sent on for

grading. Associate examiners did the

first reading, formulating initial recommendations on whether to pass or fail a

paper, with comments in blue ink. The

chief and deputy examiners usually read only those papers recommended as having

sufficient quality to pass; at this stage, only black ink was used.

About one percent of candidates passed. The imperial government in each province

showed the victors special recognition.

From then on, they wore a special hat knob, kept a flag staff in front

of their family residences and hung a tablet over their doors, announcing the

home of a literary prizeman.

The final step in the examination process was the

metropolitan exam. It was held in much

the same way as the provincial exam.

Examiners, personally appointed by the emperor, had to retire to the

examination on the day of their notification.

The compound was secured just as for the provincial exam. Frequently, more than ten thousand candidates

were summoned. As before, the procedure

was conducted in phases. From this

select group, about 300 typically earned a place in the bureaucratic apparatus.

|

|

|

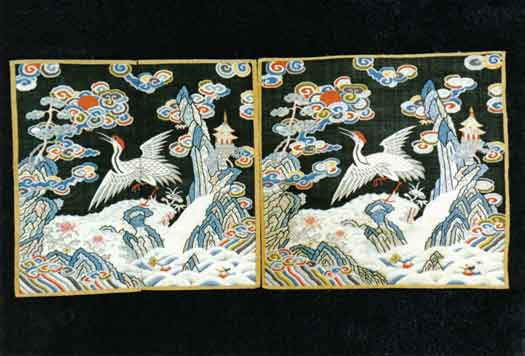

Cranes, mid-18th century |

The examination system was not ideal. Submissiveness before authority, learned by

young students while memorizing the classics, presumed the sacrifice of

individual creativity in favor of the already known and accepted. The system served to single out the best

minds among the population and sharpen their interest in attaining the status

quo. Concurrently, this minimized the

possibility of revolt or discontent.

Legitimacy was imparted to the emperor, whoever he might be, through the

aura of respect the mandarins bore in the eyes of the populace. In addition, the bureaucracy was rife with

corruption, with more than 95 percent of the mandarins’ income stemming from

bribes and payoffs.

Yet despite the host of drawbacks, the system of state

examinations established in China was the first and most developed in the

civilized world. It provided an outlet

to seek and achieve success regardless of origin. The equitable treatment shown participants

cleared the way for even a poor boy to reach the highest posts of state

power. For centuries, education, as the

only road to success, formed the exclusive focus for the population in trying

to improve their lives. The system also

served to identify the most talented representatives of the populace for the

privilege of administrative governance in the name of the Son of Heaven, placing

his unchecked will under a certain control that obliged him to consider the

options, opinions and recommendations of a group somewhat independent of the

need for imperial favor. The

examinational institution in China remains an example of how even under

authoritarian rule the democratic process can emerge and exert influence,

illustrating the opportunities to be gained through total commitment and hard,

ambitious work. Today, too, the ordinary

oriental student’s purposeful fervor, similarly focused on education, has a

quality absent in genealogies less marked by reverence for the all-conquering

power of knowledge.

All contents © Apraksin

Blues/Все

содержания © Апраксин

Блюз.